Tuesday, July 26, 2005

Book Review: David Herlihy, Bicycle: The History

I recently finished reading David V. Herlihy, Bicycle: The History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004) It is a detailed, readable, well-illustrated account that is worthy of being considered the new standard, definitive history of the bicycle's early technological development. Despite a concluding Part Five that examines the twentieth century, the focus is squarely on the nineteenth century and the machine's evolution on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. Technological innovation and change is Herlihy's primary concern, with social impact being secondary. But he does a good job of linking the two in a dialectical way.

I don't wish to be truly critical of the book, although I personally would have preferred something where social history was the primary concern, with bicycle's development set against a much larger social-cultural context. Herlihy does this only to a limited extent. For example, he notes throughout the emancipatory role the bicycle played for women, children, and the working classes--all the way back to the "boneshaker" era of the 1860s--but he doesn't offer a full appreciation of how the bicycle's social impact meshed with other contemporary social, technological, and economic changes. Again, these are more concerns out of personal taste and the kind of book I would have wanted to read, rather than criticism of the truly fine story that Herlihy does in fact provide. Here's my simple summary:

During the 1800s, there was a long multi-pronged effort to provide a mechanical alternative to the horse. Following numerous other failed attempts, many involving more than two wheels and designed to carry more than one person, the relatively simple running machine--known variously as the "laufsmachine", "draisine", or "velocipede"--of the German baron Karl von Drais made a significant splash in 1817. Its popularity as anything more than a mere curiosity lasted only a couple of years, but it nonetheless inspired numerous tinkerers on both sides of the Atlantic (US, England, France, primarily) to continue searching for a workable bicycle--two-wheeled personal transportation--in the decades that followed.

This search came to an end--or at least another major watershed--in the 1860s when a number of competing Frenchmen designed true, crank-driven bicycles. The most famous of these early developers was the Parisian blacksmith Pierre Michaux who in 1867 began offering to the public his new "pedal velocipede". This spawned the first of the true bicycle crazes that the world has seen, with Paris and France more generally very much at the center. While the machine's popularity would wax and wave ever after, from the 1860s on, bicycle racing was an established sport. The lack of suspension and gearing on these early boneshakers, however, kept the machine from being the ubiquitous, egalitarian personal transportation that many had envisioned.

The next phase of development centered around the giant high-wheelers of the 1870s, which provided a much faster and smoother ride than the smaller-wheeled boneshakers of the 1860s. But these elegant machines were notoriously expensive and difficult to master, and cycling remained a leisure activity for the physically and financially well-off. That all changed in the 1880s--a "volatile period in bicycle history" (p. 225)--with the advent of the modern "safety" bicycle characterized by geared chain drive (and thus smaller wheels) and, as of 1891, detachable pneumatic tires pioneered by none other than Edouard Michelin. The result was a true "bicycle boom" in the 1890s that for the first time saw the bicycle begin to fulfill its promise of ubiquitous personal transportation for the masses. The bicycle's preeminence would prove to be short-lived, however, as it would soon face new competition from motorized vehicles. This was especially true in the United States, where the bicycle fell out of fashion as soon as it became accessible to the working classes. Its place as a very practical means of everyday adult transportation remained more intact in war-torn Europe through the 1950s, although today it is primarily in less-developed countries where one sees the bicycle widely used in this role. Somewhat ironically, in wealthier countries such as the United States, bicycles for adults are regaining their historic place as rather costly recreational toys for the physically-active affluent. This recreational renaissance owes much to the various fitness crazes of the latter 20th century, tied both to the rise of trail-oriented mountain bikes and to the prominence of American racers such as Greg LeMond and Lance Armstrong. For those with a California interest like me, our Golden State has played a central role in many of these recent developments, including the rise of mountain bikes (NorCal) and BMX (SoCal) during the 1970s, as well as a rather different cycling craze in the early 1930s when Hollywood figures--most notably the couple Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. and Joan Crawford--led the way in promoting cycling as a healthful and fun outdoor activity.

All in all, this is a book that any bicycle enthusiast or anyone else interested in machine-age history would very much enjoy.

Monday, July 25, 2005

Pete's World Cycling Rankings

With the advent this year of the new Pro Tour, the UCI's old system of rider rankings has been replaced by a new system characterized by two big changes: (1) Only official Pro Tour events now count, and points are, in general, harder to come by. (2) Rather than based on a revolving calendar that takes into account the previous 12 months of results, only results in the current calendar year are now tallied. In other words, every rider starts the new year afresh at zero. I personally don't have a big problem with change #1, but change #2 means the Pro Tour rankings provide a rather strange accounting of who the world's best cyclists are, especially during the first half of the year when the list of completed events is small. Add to this concern the fact that no points system is going to be perfect, inevitably undervaluing some performances (e.g., stage wins) while overvaluing others, I've decided to offer my own, very subjective ranking. With the Tour de France now complete, I figure it's time I unveil my first official Top Ten. Look for my next ranking at the end of August, during the early stages of the Vuelta.

Pete's World Cycling Rankings (July 25, 2005)

1. Lance Armstrong (current Pro Tour standing = 2)

2. Danilo Di Luca (1)

3. Tom Boonen (4)

4. Alexandre Vinokourov (3)

5. Ivan Basso (12)

6. Alessandro Petacchi (5)

7. Paolo Salvodelli (9)

8. Paolo Bettini (41)

9. Bobby Julich (16)

10. Damiano Cunego (27)

Top Team: Discovery Channel, with honorable mention to CSC, Phonak, and Quick Step

I'm not really a Lance Armstrong fan, but seven tours speak for themselves, and it seems a no-brainer that the greatest TdF rider of his or any generation retire from the sport ranked #1. Even if he were not retiring, though, he wouldn't last long atop my list for the simple reason that he has made himself the Bjorn Borg of cycling. Despite possessing incredible all-around skills, just like Borg at Wimbledon during the 1970s and '80s, every July Armstrong takes center stage with a dominant performance in his sport's annual marquee event, only to disappear into relative obscurity the rest of the year. That was actually less true of Borg than of Armstrong, as the Tour really stands alone in cycling today--particularly from a U.S. vantage point--while Wimbledon is perhaps a "first among equals" when compared to the other three Grand Slam events. While Armstrong's choice to focus solely on the Tour is entirely defensible, especially when it results in an unprecedented string of seven victories, it's nonetheless been frustrating for cycling fans. The Giro, the Vuelta, the World Championships, the Olympics, the spring and fall classics, have all suffered from Armstrong's absence, and his unwillingness to even contest these events will inevitably tarnish his legacy in the sport. Indeed, in a sport whose fans value more than anything else spontaneous displays of courage and a willingness to fail, the superbly talented and dedicated Armstrong will always be remembered as much for what he didn't even try to accomplish as for the incredible feats that he did. Retiring "early" before actually being dethroned by another champion only adds to that legacy.

As for the rest of my inaugural top ten, Danilo Di Luca and Tom Boonen have already had dream seasons and promise to deliver even more stellar results this fall. They were the two dominant figures in the spring classics--Boonen on the cobblestones of Flanders and Di Luca in the hills of Wallonia--and then Di Luca shined even brighter in the Giro while Boonen was the dominant sprinter early on in the Tour. Not far behind these two riders is Alexandre Vinokourov; after something of a slow start this year (for him and his T-Mobile team), he delivered a brilliant win at Liege and then animated the Tour like no other rider, not even Armstrong. With strong rides at both the Giro and Tour, Ivan Basso looks on target to replace Armstrong as the world's best grand-tour rider, while Alessandro Petacchi still deserves to be called the world's greatest sprinter, with a Milan-Sanremo win more than compensating for a somewhat subpar (by his recent standards) Giro. Paolo Salvodelli is enjoying a dream comeback season, with a Giro victory and Tour stage win to his credit. Paolo Bettini, on the other hand, has been relatively quiet this year, but the Olympic champion and three-time winner of the now-discontinued World Cup was the "Vinokourov" of the Giro's first week. Rounding out the list are the rejuvenated Bobby Julich, winner of Paris-Nice and Criterium Internationale early in the season and more recently a very solid contributor to Team CSC's efforts in the Tour; and illness-slowed Damiano Cunego, the young Italian star who finished his dream season last year ranked #1 in the world and did just enough in the early stages of this year's Giro to remain in my top ten.

Honorable Mention honors go to the following (in alphabetical order):

Santiago Botero (7) -- has rejuvenated his career at Phonak

Oscar Freire (8) -- reigning world champion

Roberto Heras (not ranked) -- reigning Vuelta champion

George Hincapie (10) -- KBK, Roubaix podium, stage win and top 20 at the Tour...best year ever for arguably the greatest helper of all time; a true superdomestique

Levi Leipheimer (15) -- solid efforts at the Tour and the Dauphine, but it's about time he actually won something

Robbie McEwen (68) -- Petacchi's only real rival in the sprints; the Pro Tour points system doesn't do him justice

Davide Rebbelin (11) -- last year's Di Luca who rather quietly has ridden almost into the 2005 Pro Tour's top ten

Gilberto Simoni (19) -- proud former champion of the Giro who's done much to animate that great race the last two years

Jan Ullrich (6) -- the Simoni of the Tour

Alejandro Valverde (32) -- Spain's answer to Cunego; could he have ridden with Lance all the way to Paris if not for the bum knee?

Thursday, July 21, 2005

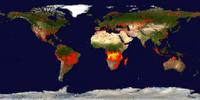

NASA's World Fire Map

NASA has recently provided us with its latest composite look at fires around the world detected by a pair of remote-sensing satellites during their orbits around the earth in the first 10 days of July. As you could probably figure out, the red dots mean a few fires, while the yellow dots mean a lot of fires. It's a pretty dramatic picture (probably too dramatic) at how forests and grasslands around the world--particularly in the tropics--are literally ablaze. Fire undoubtedly remains humanity's oldest and most powerful tool for transforming landscapes and ecosystems, a tool that is all the more powerful because it is a natural phenomenon that we've only partly domesticated.

NASA has recently provided us with its latest composite look at fires around the world detected by a pair of remote-sensing satellites during their orbits around the earth in the first 10 days of July. As you could probably figure out, the red dots mean a few fires, while the yellow dots mean a lot of fires. It's a pretty dramatic picture (probably too dramatic) at how forests and grasslands around the world--particularly in the tropics--are literally ablaze. Fire undoubtedly remains humanity's oldest and most powerful tool for transforming landscapes and ecosystems, a tool that is all the more powerful because it is a natural phenomenon that we've only partly domesticated.

Vacation Photos

It's been several weeks since my last post as my family and I have been enjoying some summer fun. This most recently included a week-long trip to the extended Bay Area, with a few days each spent in San Jose (home to my in-laws) and Aptos (my sister's wedding, and thus now home to her in-laws). A few dozen pictures from the trip are now readily viewable at my Flickr site:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/californiapete/

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)